Steven Hill & the Long Run

Steven Hill Barbara Bain Martin Landau

Steven Hill Barbara Bain Martin Landau

Steven Hill Barbara Bain Martin Landau

Steven Hill Barbara Bain Martin Landau

BILL STERN

BILL STERN

CLEM McCARTHY

CLEM McCARTHY

Recently college and professional football player Jack Zilly passed away. His passing brought to mind a tale that involved 3 of the most honored sportscasters of the 20th century, each a member of the Sportscasters Hall of Fame. Zilly though not a legend of sport had a part in inspiring one most famous lines in the history of sports.

When I heard this story some years ago, I thought the names seemed so unusual that they might have been made up, but with the passing of Mr. Zilly, I see that they were perfectly true. The moment in question occurred in a 1946 football game played by Notre Dame. That year Notre Dame would go on to win a national championship. Two of their best players were wide receiver Zilly and college football Hall of Fame halfback, Emil “Red” Sitko. Both men were heroic figures, not for their football deeds, but as each had returned from service in WWII to play college football. Zilly had interupted his college career, and Sitko had postponed his.

This particular game was being broadcast to the public by another Hall of Famer, sportscaster Bill Stern. Stern was a wonderful talent, but made some very famous mistakes along the way. In this game he relayed as to how Zilly had taken the ball and made a great 80 yard run slashing through opposing would be tacklers, only to lateral the ball to Emil Sitko close to the goal line, with Emil then scoring the touchdown. Zilly’s extraordinary generosity seemed almost beyond comprehension, and it was.

In this time before television, the game was presented to the public on radio. Stern described Zilly’s incredible run in glorious terms, only to agonizingly realize, he had misidentified the runner. Suddenly as the runner crossed the five yard line, Stern yelled out, “Zilly’s just thrown a lateral to Sitko!” Without the benefit of television viewers, it was some time before Stern’s subterfuge was uncovered. But, there’s more.

The next year in 1947 another very fine sportscaster made a much more embarrassing, and apparent error. The great Clem McCarthy called the wrong horse as the winner at the Preakness. Late in the race, a standing room only crowd of patrons occupying a platform had partially obscured McCarthy’s view, as two horses ridden by jockeys wearing similar silks exchanged positions in the stretch. Despite his own error of the year before, Stern kidded McCarthy for years about that, a situation that caused another very talented member of the profession, Ted Husing, to harbor some animosity toward Stern. In 1949 when Stern and Husing were both working for the same radio station, and Stern had been given the assignment of calling races from Belmont Park, Stern asked Husing, who was more experienced in calling horse races, if he had any advice. Husing tersely replied, “I can’t help you, Bill. There’s no way to lateral a horse.”

Mr. Zilly also was involved in another somewhat unique event, being drafted into the NFL by a team in one city, but beginning his career in another, though he never actually left his first team. The situation reminds me in a way of the story of my grandfather Reuben. He told me that he was born in Austria and later emigrated to this country from Poland. When I asked him when he moved to Poland, he told me, “Oh, I never moved, the countries just moved around me. I lived in the same town all of my life before coming to America.” Well in the case of Zilly, he was drafted by the Cleveland Rams, but by the time he would report for duty the team had moved two thousand miles west and settled in L. A., though that too was not very permanent.

A little Dodgers baseball quiz. Who is the only singer to appear at a Dodgers home game in Sandy Koufax’s first year, 1955 and his last, 1966. And who is the only singer to sing at Dodger games in their home ballparks in 3 different cities. You might say, wait a minute the Dodgers only played in 2 cities. Well you might say that, but you’d be wrong. And the answer, well, it was Eddie Fisher. Not a surprise if you looked at the title of this article.

Most people are aware that the Dodgers played in Brooklyn at Ebbets Field and in L. A. at Dodger Stadium (and also at the Coliseum), but only a relative few know that the Dodgers also played some of their home games in New Jersey in 1956 and 1957.

In 1956 the Dodgers played 7 of their home games at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City and in 1957 they played 8, about 10% of their schedule. At one point Walter O’Malley even issued a statement that if there was no new stadium built in Brooklyn that he might play the entire 1958 season in Jersey City. Well, he did desert Ebbets Field in 1958, but he moved the club a little further west. One interesting side note was that while the Dodgers had their top farm team in the Northeast, the location of the stadium and the city they played these games in, was actually the home of the Giants highest level farm club.

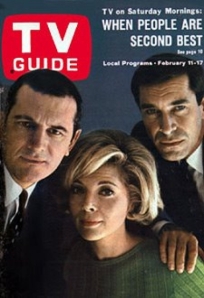

The picture above is from May 31, 1955, when it was Eddie Fisher day at Ebbets Field. In the photo Eddie is being presented a plaque noting that momentous occasion by Dodger great Pee Wee Reese. Eddie also sang at Dodger Stadium during the 1966 World Series. And on April 19, 1956, Eddie Fisher sang prior to the game as the Dodgers played their first game ever in Jersey City and raised their 1955 World Championship Banner, the only one they would earn while in Brooklyn, above Roosevelt Stadium. Quite a game took place that day as the Dodgers defeated the Phillies by a score of 5-4 in 10 innings, pushing across two runs in the bottom of the 10th, after allowing the Phils one in the top of that inning.

I guess Eddie Fisher was good luck for the Boys in Blue. In each of the years mentioned above the Dodgers were World Series participants. And Fisher was quite a talent as well. His powerful and thrilling voice, combined with a dynamic and emotive style, earned him gushing reviews and enormous popularity. During his hey day in the 1950s he set a record that still stands for most Top 10 hits by a solo artist.

And his good looks and boyish charm earned him the love of 3 of Hollywood’s most glamorous stars, as Debbie Reynolds, Elizabeth Taylor and Connie Stevens consecutively became Mrs. Eddie Fisher. Examples of his vocal artistry abound on youtube.

In 2004, just as the season was about to get under way the Dodgers acquired Jayson Werth from Toronto. In June of that year he became their regular centerfielder, demonstrating the power hitting and fielding skills he would later showcase elsewhere. In that year the Dodgers made their first post season appearance since 1996 and Werth started each of those playoff games. In the initial spring training game of 2005 the Marlins A. J. Burnett hit Werth with a pitch and fractured Jayson’s left wrist. Werth was able to come back for a time, but the injury, diagnosed as an avulsion fracture, did not heal and he wound up missing about half of the season. And even when he did play, the on going pain greatly effected his on field performance. After the season the Dodgers sent him to their hand specialist who performed an operation and it was expected that Werth would be ready for spring training in 2006.

2006 rolled around but the pain continued, and after trying very hard to play Werth found himself still unable to perform on the field. The Dodgers doctors re-examined Jayson and couldn’t find anything wrong. They told him just to keep himself in good shape and let them know when the pain subsided to the point where he could play again. As the weeks went on and no progress occurred Werth was sent out to get a raft of second opinions, treatments such as cortisone shots and various therapies, but nothing seemed to help. Eventually Jayson was sent home and told to return when healthy enough to play.

With August suddenly upon him and no improvement in his condition, Werth happened to run into a family friend, an orthopedic surgeon, who recommended he go to the Mayo Clinic and see a wrist specialist. At the clinic Dr. Robert Berger examined Werth and determined that he had a condition that was often misdiagnosed, and had been in Werth’s case. The next day Berger performed surgery on what turned out to be a split tear in a wrist ligament. After 12 weeks combined of being in a cast and then subsequent rehabilitation, Werth was at last pain free.

He contacted the Dodgers to tell them that he had finally found a doctor who had correctly diagnosed his problem and who was confident that the outfielder would recover fully. Though due to their great regard for his potential, the Dodgers had kept him on salary for 2 years, during which time he had played little, by this time the Dodgers had become convinced that Werth would never recover and released him. Contributing to that poor judgement on management’s part was the fact that the Dodgers had changed both the General Manager and the Manager coming into the 2006 season. And thus both those who best remembered what a healthy Werth was capable of, and those who were in the strongest position to argue for his continuing with the team, were no longer present. The Phils signed him in 2007 to a one year deal for a modest salary, and have reaped the benefits since.

So Phillies fans, you owe a great deal to the Dodgers team hand specialist for his misdiagnosis. And don’t boo A. J. Burnett too badly during the series, for he rendered an invaluable service as well. Were it not for the pitch he threw that resulted in Werth’s injury, Jayson would still mostly likely be roaming the outfield for the Dodgers and the Phillies would presently be awaiting spring training 2010. A Dodgers outfield of Werth, Ethier and Kemp would be among the most talented in baseball, and very probably the most athletic.

Sadly on April 13, 2009 the baseball world, and especially Phillies fans lost a great announcer and baseball man, Harry Kalas. For many years Harry worked with Phillies Hall of Fame ballplayer Richie Ashburn who passed on in 1997. Harry always referred to Ashburn as Whitey and the two men became great friends. I want to share two stories about this partnership, one was Harry’s favorite story about Whitey and the other is from my own experience.

Harry Kalas loved to tell this story about his old friend and booth mate, so here goes. “One of Whitey’s responsibilities when he was broadcasting for the Phillies was doing the pregame show, taping an interview with an opposing manager or player or coach. He’d take his tape recorder down to the clubhouse and get an interview and he’d come back up. He’d say, ‘Boys, that might be the best interview I ever had.’ He’d hand the tape machine to the technician and the tech would say, ‘Whitey, there’s nothing on here.’ I mean, if this happened once, it happened 50 times. “And Ashburn would then have to scramble out of the booth, go find the first warm body and try to do an interview for the pregame show.”

|

I was at the library the other day and saw a book on a table entitled Call Me Lumpy. Being the big Leave it to Beaver fan that I am, I decided to peruse the tome. And I was well rewarded for my efforts. The book which came out in 1997 is the biography of Frank Bank, who played Lumpy on the show. He was born in 1942 in L. A. and started acting at an early age. In one section he talks about his father and reveals the following.

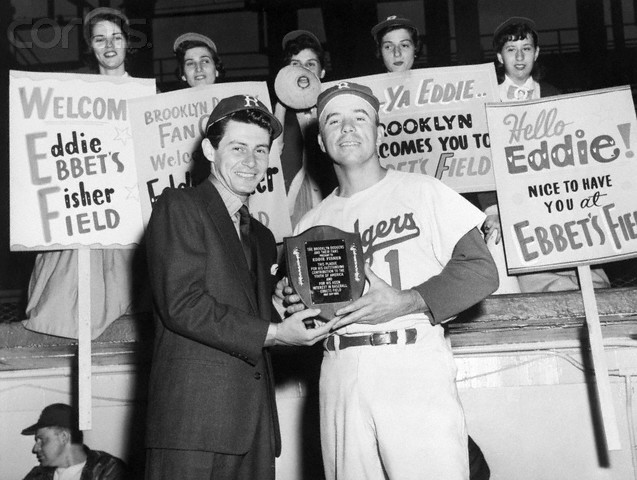

Frank says that his father Leonard used to take him to Gilmore Field in the late ’40s to watch the Hollywood Stars minor league games. Major League baseball had not yet come to California. He said that they used to sit right behind Al Jolson and became very friendly with him. He says that Jolie used to bring a large basket to the games filled with 5 pound salamis and rye bread and also pickles and a big pot of potato salad. Jolson had a block of 50 season seats that he had purchased right behind the Stars’ dugout which he filled with cronies. He adds that the usual attire for the crew was straw hats or fedoras and pants held up by suspenders, no jackets, no ties.

Bank says that Jolson was very friendly and constantly joking with everyone. He says that while his father could not properly be called a friend of Al’s, that Jolie would always greet him with a “Hi Len, how are ya?” and let him sit somewhere in that 50 seat block. Bank says that it was a kind of king and his court atmosphere, as Jolie’s pals would seek his favor and cater to his whims, getting him beers and other things he might want. Frank says that on occasion Jolson would turn towards him and bark, “Hey kid go get me some sodas.” He says that he was thrilled to run errands for Al and that he would usually bring back a case of sodas.

Bank continues that Jolson would keep up a running commentary and critique of the players. He says that Jolson loved to get on the players and that they would yell things back. He says that once Jolson had been riding one of the Stars’ players pretty hard. During that game this particular player hit a home run. When the player reached home, instead of coming in standing up, he slid in and then popped up onto one knee, hands out stretched Jolsonlike, as if to say, take that wiseguy. Bank says Jolie cracked up at the sight of this, as did most of the crowd. By the way Jolson co-hosted pregame ceremonies with Jack Benny, Robert Taylor Gary Cooper and Bing Crosby when Gilmore Field opened in 1939.

Later on Frank talks about the death of his father and how being Jewish he wanted to be buried at Hillside Memorial Park. He says that his father always said, “Son, all I ask is that you make sure I’m next to Jolie.” Frank says that it took a lot of doing but that his dad currently resides on a certain hillside, not 20 feet from Jolson.

For those Beaver fans, a little trivia.

1. Frank Bank is the actor’s real name

2. Bank says that he, Ken Osmond, Tony Dow and Jerry Mathers have remained close through the years.

3. He says that Hugh Beaumont and Barbara Billingsley were like parents to the four mentioned above and two of the nicest people he has ever known.

4. Bank says that he met many big stars while acting, guys like John Wayne and Cary Grant, and they were consistently nice to him. He says the only jerk he encountered was Marlon Brando.

Mike

|

Bernhard “Barney” Dreyfuss immigrated to a nation not particularly hospitable to Jews and succeeded magnificently in a sport not any more inviting. Dreyfuss was a German Jewish immigrant to this country who was born in 1865 and arrived in America in 1882 at the age of 16 so as to avoid conscription in the German army. He settled in Paducah, Kentucky where he found employment as a bookkeeper in a bourbon distillery. He worked long hours and a six day week as well as attending night classes so as to learn English. This schedule overtaxed his frail constitution and a doctor advised he get some outdoor activity. He then proceeded to form a semi-pro baseball team on which he played second base. In 1889 the distillery expanded to Louisville, Barney came along and over time he invested his savings in the Louisville Colonels baseball team which entered the National League in 1892. After the 1899 season the league contracted by four teams, one of which was Louisville. Barney with borrowed funds acquired a half ownership in the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1900, and brought with him from the Louisville team three future Hall of Famers, Fred Clarke, Honus Wagner and Rube Waddell.

During his years of ownership the Pirates were very successful. They won pennants in 1901, 1902, 1903, 1909, 1925 and 1927. In 1909 they beat the Tigers of Ty Cobb and in 1925 they bested the Senators of Walter Johnson for world championships. In 1902 the Pirates won the pennant by a record margin of 27 1/2 games which has still not been surpassed. In 1903 Dreyfuss brokered a peace between the rival National and American Leagues, arranging for the first World Series. One of the rules he negotiated was that rosters could not be changed after September 1, a rule still in effect. The Pirates lost to the Boston Pilgrims, but Dreyfuss donated his entire share of the receipts to his players and the Pirates became the only losing team in history whose players received more money than the winning side did. He also offered to invest his players salaries over the years guaranteeing to make up any losses.

The Pirates probably should have won that initial series in 1903, but Dreyfuss encountered some incredible bad luck shortly before play began. Two of his three top pitchers suffered great misfortune. Sam Leever who had won 25 games and led the league in ERA was injured in a shooting accident and was largely ineffective during the series. Ed Doheny, in the terminology of the day, went berserk in late September, was committed to an insane asylum and never pitched in the major leagues again. This left Deacon Phillippe who started 5 of the 8 games played. He won games 1, 3 and 4, but wore down losing games 7 and 8.

In 1904 Barney was so angered by John McGraw’s refusal to allow his pennant winning Giants to play the American League champs, in effect killing the World Series, that he arranged for the so called Fourth Place Series to be played. Though not official post season games, Dreyfuss had his fourth place Pirates to play the club finishing fourth in the American League, and fans were treated to a group of games in which they could see the two batting champs, Honus Wagner and Cleveland’s Napoleon Lajoie. In 1909 Dreyfuss built the first concrete and steel triple tier stadium (Forbes Field) with the then unheard of attendance capacity of 25,000. His critics labeled it Dreyfuss’ Folly claiming no park that size could be filled, but on opening day over 30,000 showed up. Dreyfuss refused to allow ads to be placed inside the ball park for he did not want to spoil the beauty of the field of play and the fan experience, thus foregoing over one million dollars in revenue. He also led the fight to rid the sport of gamblers and to institute the position of commissioner and indeed Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ appointment is considered one of his legacies.

Dreyfuss turned over the running of the team to his son Samuel in 1930, but unfortunately the 34 year old died of pneumonia in 1931. Barney took over the team again that year but died in 1932, ironically of the same malady. In the 33 years Barney Dreyfuss owned the team the Pirates and excellence were synonyms, something that obviously cannot be said today. He also probably deserves enshrinement in the Pro Football Hall of Fame as co-owner of the nation’s first professional football franchise, the Pittsburgh Athletic Club, which captured the league championship in 1898.

Getting back to baseball, Branch Rickey called Barney Dreyfuss, “the best judge of players he had ever seen.” The President of the National League in Dreyfuss’ time, John Heydler, said that, ” Barney Drefuss discovered more great players than any man in the game.” In addition to the players mentioned earlier, Dreyfuss brought to the Pirates Hall of Fame players Max Carey, Pie Traynor, Paul and Lloyd Waner and Hazen “Kiki” Culyer. When columnist Bob Ryan of the Boston Globe heard of Dreyfuss’ election to the Hall in December 2007, he wrote that, “his exclusion from the Hall of Fame all these years was the single most baffling and inexplicable oversight among all non-playing personnel in the 20th century. That’s a big statement, and I’m prepared to back it up.”

There is one more thing to be said of Dreyfuss that concerns his incredible desire to win, but his even steelier determination to be true to his sense of honor and dignity. During the 1927 series against the Yankees a great mystery enveloped the baseball world. The Pirates lost the series in four games but the series was closer than one might suppose, with two games being decided by a single run, with the deciding game four going to the Yanks on a wild pitch in the bottom of the ninth. The mystery was why the Pirates star outfielder, Kiki Cuyler, was not seen for even one play. During the series Wilbert Robinson, manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers (or Robins), was writing a special column for the New York Times and proclaimed his puzzlement at Cuyler’s absence, saying it certainly handicapped the Pirates on defense. The Times talked of the “Cuyler Case” stating ” discussion of which weighted all conversation and writing on the world series.” The Times also said. “Cuyler warmed the bench much of the season and the whole of the world series, despite the strident yells of Pittsburgh and New York spectators demanding that the man who won two of the 1925 world series games be given a chance to show his stuff.”

The Times also noted that the “Cuyler Case” “had shaken Pittsburgh fandom to its foundations.” In game 2 the Times went on that, “the fans staged one of the most remarkable demonstrations seen in any world series.” And continued saying the following. “The patience of Pirate fans was exhausted today at the continued absence of Kiki Cuyler from the line-up and the star outfielder was made the the hero of one of the greatest popular demonstrations ever witnessed on a ball field. In the eighth inning with the home team trailing, the Pirate fans rose en masse and demanded that manager Donie Bush send Culyler in to bat for the pitcher. The cries lasted for several minutes but fell on deaf ears.”

After the series was over Cuyler said that as Manager Bush and Barney and Sam Dreyfuss had given some reasons during the course of the season for his not playing, so he would explain his understanding of the matter. He said that Bush had requested he move to left field and change from batting third to second. Cuyler said he complied, but added that he felt he was not suited to bat se

cond and said that playing left was the worst thing he did. Cuyler also noted that he had been fined $50 for not sliding into second base to break up a double play. He said that he went in standing up, as he felt that, that was the correct play at the time. He also noted that the first year manager Bush had in one game instructed him to take a big lead off third. Cuyler said he had protested at the time that he thought this was dangerous and after being caught off the base had been, he felt, unfairly berated by Bush. Cuyler said that he hoped to remain with the Pirates, but felt that he had probably played his last game in Pittsburgh.

Most in the baseball world thought that Cuyler’s limited playing time was an over reaction to his alleged indiscretions, but Cuyler had left out an important part of the story. Some months after the series a Pittsburgh newspaper revealed that Cuyler’s frustrations with his decreased playing time due to his disagreements with manager Bush had resulted in a violent reaction. It was discovered that one day Cuyler had let loose with a stream of anti-Semitic invective directed at Dreyfuss’ son Sam. Though this may have cost the Pirates a championship, Barney directed that Cuyler not be used during the series. In November Cuyler, the team’s best player and a future Hall of Famer, was traded to the Cubs.

Two notes. While researching about that 1927 series I found two items that show a clear difference from the modern era. On October 11, the New York Times noted that just three days after winning the series Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig played an exhibition game in Trenton, N. J. against the Brooklyn Royal Giants. In this opening game of the barnstorming season Ruth crashed 3 homers. And shortly after winning the series team owner Colonel Jacob Ruppert received the following telegram from American League president Ban Johnson. “Hearty congratulations to you, manager Huggins and the players. We like to destroy the enemy in that manner. Four straight victories will have a wholesome effect on he public mind.”